The Great War and the Good War

Conversation:

Man I am playing through the BF1 campaign finally which I would describe as "effective" or possibly even "ruinously effective"

> Mmmm?

It manages to feel very viscerally awful. I think it does a good job of making everything I do feel both very important to the mission and my unit while also incredibly pointless and wasteful, which seems appropriate. It’s interesting that Spec Ops was like “a game about how much war sucks” and BF1 is “a game about war, which inherently sucks.”

I do think I guess WWI is old enough in historical memory that it is politically correct to acknowledge how much it sucked and WWII is not quite to that point.

> Mmm. I’m not sure if I would say that WWII is more Just but it definitely was… maybe less belligerently complicated?

> Also I should sleep, as interesting as this is

Well, yeah. But at the end of the day it was still a lot of young draftees dying in newly horrible ways for empires they had no real say in. The numbers are just staggering. 35,000 Me 109s built. 18,000 B-24s. Just tens of thousands of potential plows or railcars or houses or anything else being reduced to shrapnel and unrecognisable pieces of 19-year-old. That’s what I meant about “inherently sucks” though, not conspicuously, I think the way WWI is in collective consciousness.

Yeah! Sleep! I may or may not ramble at you while you sleep.

Rambling:

I think one reason WWI is “safer” as a way to explore “fucking hell, war is incredibly fucking pointless and stupid and destructive” is because that’s sort of built into the war’s narrative arc: it was the war that started out with “For King and Country!” and left a shattered husk of a world in its wake. World War II didn’t get to start that way. There’s nothing that really approaches the pathos of, say, Kipling being an aggressive pro-war propagandist and having his only son1—whom his wife had strongly opposed enlisting—die somehow, somewhere at Loos without his body even being recovered.

This was a war enthuiastically undertaken—“Pals’ Battalions” formed of local friends and community folk, in recruitment lines stretching around the block. Kitchener’s Army, the all-volunteer groups raised early in the war, bought their own field manuals and uniforms until official ones could be supplied, and “trained” through 1915 with drill rifles that could not be fired and Napoleonic-era cannon scavenged from museums. That September, they first saw fighting at Loos, a battle about which IV Corps commander Sir Henry Rawlinson reported to General Haig:

From what I can ascertain, some of the divisions did actually reach the enemy's trenches, for their bodies can now be seen on the barbed wire.

Many of the officers had been promoted only the month before; 9th Division commander Thesiger went from colonel to major-general, a 12-fold increase in the span of his command, in only a year. 18,620 soldiers died alongside Lieutenant Kipling; Haig abandoned the offensive six weeks later, having accomplished nothing. Modernism reacted to WWI with the absurdism that comes from being so thoroughly jarred out of complacency—as Yeats put it: “the darkness drops again, but now I know / that twenty centuries of stony sleep / were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle / and what rough beast, its hour come ‘round at last / slouches towards Bethlehem to be born.” There is a clear sense of shock at the reversal of the early optimism of a war over by Christmas yielding way to the reality of the Somme.

And you see that transition itself in the literature, the slow recognition of futility in All Quiet on the Western Front or of the self-awareness of how the state has betrayed the man in Johnny Got His Gun. By contrast WWII popular literature is aburdist from the get-go; there’s no sense in Catch-22 that the war was ever logical or a thing one “enlists to fight in” any more than one enlists to experience a hurricane. There’s no hint that Slaughterhouse-Five even could have been heroic, if it wanted to.

There’s a recurring theme in WWI poetry, and there was a lot of WW1 poetry, that serves as commentary on that transition itself, and I think that’s also an illustrative comparison. Look at how visceral Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est” is on that point; the bitterness of those incredible final lines. Compare that to Randall Jarrell’s equal famous “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner,” who, we sense, was never told that “old Lie” to begin with. It’s just as visceral, and just as brutal—but it lacks that sense of disillusionment and… well, betrayal, again, for lack of a better word. That generation already carried the scars of how their parents were betrayed; they needed no such rude awakening.

It helps that WWI does have a narrative arc, in a sense, albeit a post-facto one. In Germany, the “stab-in-the-back” legend2; in the UK, the “lions led by donkeys” echo, with its own subtype in the reaction of Australians and Kiwis to the Dardanelles campaign and the sense that the colonials were really abused by uncaring classists in London (c.f. Breaker Morant, which is set earlier but leverages that exact same sentiment because Gallipoli was starting to get its fangs into the public consciousness3). The image of men being sent “over the top” into a pointless slaughterhouse is extremely potent in its absurdity and its wastefulness.

“Good-morning; good-morning!” the General said

When we met him last week on our way to the line.

Now the soldiers he smiled at are most of ‘em dead,

And we’re cursing his staff for incompetent swine.

“He's a cheery old card,” grunted Harry to Jack

As they slogged up to Arras with rifle and pack.

• • • •

But he did for them both by his plan of attack.

— “The General,” Siegfried Sassoon

But it is a post-facto one, and WWI was not unique in that regard. There is the exact same grotesque wastefulness if one imagines the operational commander at Omaha Beach deploying the amphibious Sherman tanks—watching one, after another, after another sink as soon as it was launched (of the first 29 Sherman DDs launched, only 2 even made it to shore), as surely as if they were charging into No Man’s Land at the sound of a whistle blown by one of the Great War’s donkeys.

The same absurdity tinges the Battle of Kiska—three weeks of sustained aerial and shore bombardment; a combined amphibious and airborne assault that cost 300 lives, on an island that turned out to be completely abandoned. The mechanized slaughter of the machine guns and the trenches in WWI becomes the industrial butchery of a third of a million crashed planes, and a thousand submarines at the bottom of the ocean with 8,000 merchant ships joining them4.

It is this sort of scale-defying, colossal annihilation of man and machine that leads Canadian Halifax and Lancaster pilot J. Douglas Harvey to say: “I knew nothing of [Sir Arthur “Bomber”] Harris’ grand design or of the horrible ordeal that lay ahead of me. His goal was the total aerial destruction of Germany. My goal, like that of the other kids in Bomber Command, was quite simple: to complete thirty raids, the magic number that constituted a tour of operations.”

To detail his participation in that, to remark on the exhilaration and the adrenaline and the camaraderie, and then at last to search out some evidence that it meant something—that it had happened—and to revisit Berlin, in 1961, imagining the city still leveled and discovering it rebuilt:

I spent the next afternoon walking the streets of Berlin, dodging the sleek Mercedes Benz cars, trying to remember names and recall the faces of all my friends who had died over this city on those terrible winter nights of 1943.

For the moment I could not remember them. I could not recall the terror I had felt 20,000 feet above where I now stood. I could not visualize the horrible deaths my bombs had caused here. I had no feeling of guilt. I had no feeling of accomplishment5.

And so, then, what of WWII? Of course that war also has a narrative arc, but to me it’s tied up outside combat itself. There are exceptions: I’d argue that “the triumph of technology” (cracking Enigma, rockets and jet aircraft, the Elektroboot) is one, for example. And there are absolutely combat stories that are powerful and evocative—the Norwegian heavy water raid, the Dambusters, the AVG, the evacuation of Dunkirk.

But on balance, I think that narratively WWII is less about that than it is the geopolitical impacts of the world that followed: the dawn of the Atomic Age, the Baby Boom, the Cold War, the Space Race, the Marshall Plan. If the Great War ended a world order, than the Second World War harkened the dawn of a new one. But I think that, in public consciousness, this leads to a confusion of correlation and causation.

In short: the world following WWII was better*; therefore, the soldiers in it were fighting for that world. Therefore, to some extent, the war itself was proper, and the means should be evaluated by the ends it produced—as though the two were explicitly linked. As (historian and infantry lieutenant in France) Paul Fussell puts it:

Now, fifty years later, there has been so much talk about “The Good War,” the Justified War, the Necessary War, and the like, that the young and innocent could get the impression that it was really not such a bad thing after all. It’s thus necessary to observe that it was a war and nothing else, and thus stupid and sadistic, a war, as Cyril Connolly said, “of which we are all ashamed”6

* IMO alert, and now we should get to the Hot Take

I think “better” is obviously true in many ways; it’s hard to argue anything could be worse than the Empire of Japan or Nazi Germany. But I also think that the construction of WWII in modern memory is highly driven by those post-war narratives. The exigencies of needing allies in the Cold War allowed the rehabilitation of numerous Japanese and German war criminals, but as a struggle against the spectre of Communism it also meant that war propaganda—in many ways highly corporate already, sponsored by Goodyear and Campbells and whoever wanted you to know that they were “doing their part”—carried over to the sense that WWII had been about fighting for the American way of life: i.e. conservative, capitalist, and righteous.

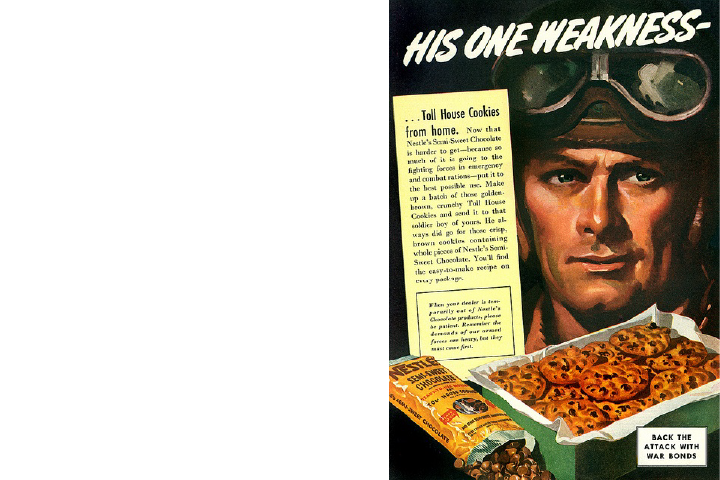

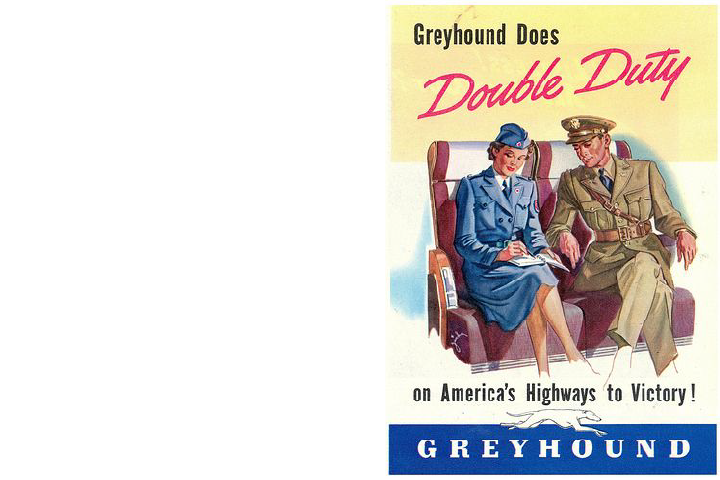

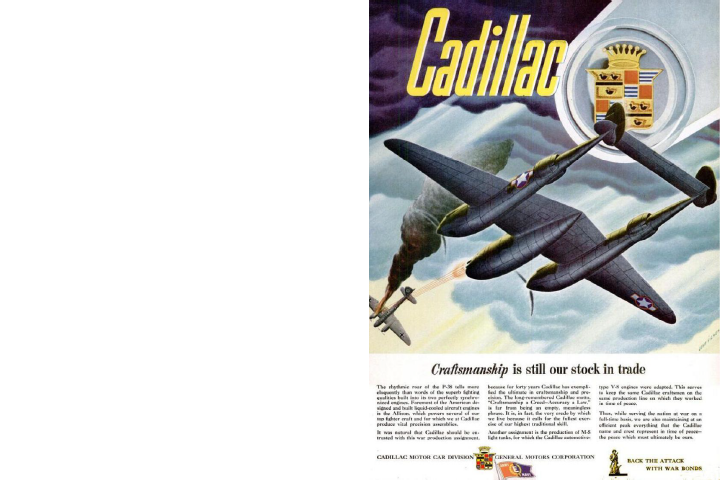

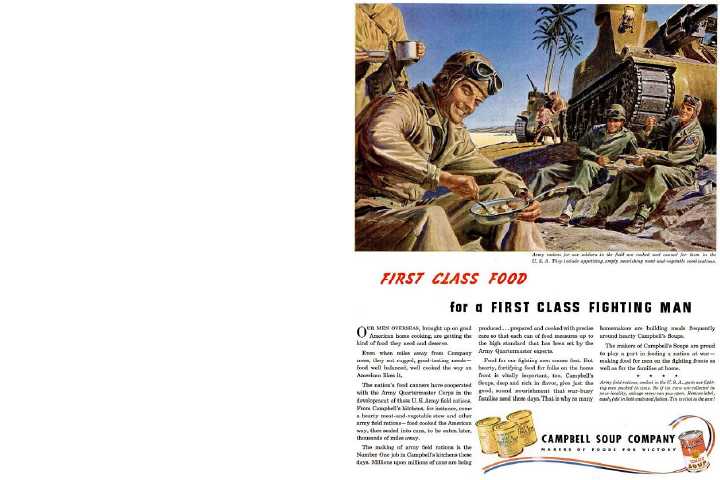

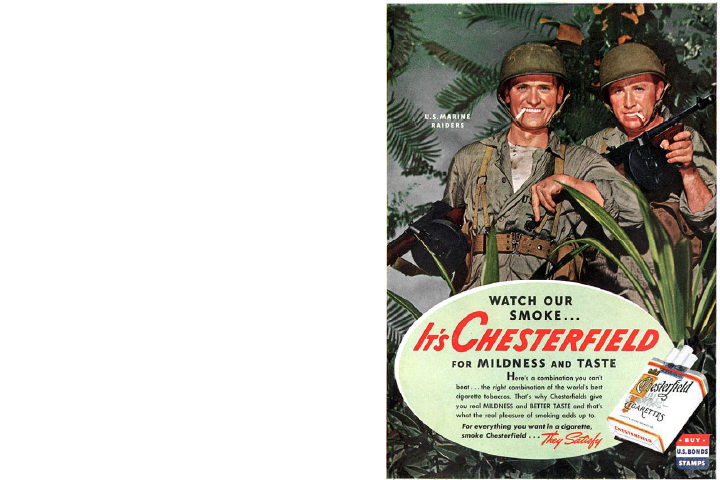

You see some pushback to this in Eisenhower’s critique of the military-industrial complex, or explicitly in Milo Minderbinder’s character in Catch-22 (the mess officer who runs it as a business, is eventually court-martialed for bombing his own base, and wins by convincing the court that capitalism is what made America great and he is merely exemplifying that ideal). But it bears noting the degree to which the war was a corporate effort, and the degree to which corporations benefited. Starting from the premise that the economic miracle of war production lifted the United States from the Great Depression, through to the messaging of the war itself, we might conclude that Minderbinder is right: capitalism is what makes America great. Tollhouse surely agrees that they’re doing their part to win the war:

And tailoring the narrative of the war served the exigencies of American racial politics. Blacks were largely excluded from an expressly segregated armed service, which meant that they were explicitly denied the benefits of the GI Bill that largely built the white post-war middle class, and implicitly denied participation in the FHA-sponsored suburban housing boom that endowed that middle class with real estate. And because they were needed for the domestic war production effort, southern Blacks experienced a huge diaspora to factories across the country where they would work during the war, and then be summarily fired when returning white soldiers with seniority took their jobs back.

Between the two, the American story of WWII is almost necessarily a hagiography of white, conservative, capitalist men employing exceptions—“Rosie the Riveter,” Doris Miller, Benjamin Davis7—in service of a narrative that is largely myth. But, more specifically, it is a myth that is extremely useful to the current of (white, conservative, capitalist, heterosexual, Christian, male) thought that was dominant in America for most of the postwar period. That makes it a little different from the narrative utility of WWI, which at least as far as Americans are concerned has no mythic purpose unless you are a US Marine.

Seen from this angle, I think it’s kind of telling that while you have some stories that are critical of the war and its participants, and the impact the war had on them—Catch-22, The Best Years of Our Lives, The Caine Mutiny, The Thin Red Line, The Bridge on the River Kwai—they almost all date from the immediate post-war period (Slaughterhouse-Five, coming out in 1969, is a late exception in the American canon) before mythologizing the experience of WWII became more useful as a bulwark against internal and external sectarianism.

None of this is to say that Allied soldiers were Bad, Actually—or even that they were not good or heroic. Some of them were Bad, Actually, of course. Even the mythologized ones—Patton can fuck right off. It’s also not to put too much emphasis on what gets omitted—the incredibly high desertion rates in the European theater, the domestic resistance to the draft, the Port Chicago mutiny, liberating the Nazi camps only to turn gay prisoners right back over to the authorities, the internment of Japanese-Americans, the sheer uselessness of terror bombing, the Zoot Suit Riots, the black markets, the inexcusable fiasco of the Mark 14 torpedo, etcetera.

These stories should be told, because they are interesting, and because they provide context to the war (especially on the home front) and the way it was experienced. None of them make WWII conspicuously “evil,” though, or imply people don’t know “the truth about WWII.” Obviously, these examples just make it complex—because there is no way a globe-spanning conflict, lasting the better part of a decade, with hundreds of millions of participants, can be anything but complex.

But I think that if you are going to make a game that conveys simultaneously the typical video game sentiment “war is exciting” but also the rarer sentiment “war is hellish and destructive and futile and awful and stupid,” WWI is a much safer setting to do that in. In his video essay on the “1776 Report,” YouTuber Shaun suggests that Americans (and to some extent British people; he’s from Liverpool) adopt a skewed view of history because of the way it is taught:

What’s the problem with centering slavery for the authors of the 1776 report? Well, it’s to do I think with the way how they view the purpose of historical education. We shouldn’t be learning from history in totality, with its moral complexities, its good and bad parts, understanding its participants as humans with human flaws and failings. What we should be doing is looking to history for patriotic and moral instruction, understanding its participants as either heroes to be emulated or villains to be defeated.

This is history as parable: we’re supposed to be being shown how best to live, and this is why conservatives often conflate discussions of their country’s historical crimes with an attack on history in general. […] We teach children about our historical role models so that they love their country. By highlighting their crimes or failings you thus must want children to hate their country.

Which I think is broadly true, and I think the degree to which commenting on the complexity of WWII—which is deeply embedded in the American psyche, and taught in a very specific way—is liable to be taken as an attack on American goodness, or an insult to the sacrifices of American servicemen, locks that off in a way that the Great War just isn’t locked off. For now, at least; that’s starting to change as the groups for whom those myths—that “history as parable”—were central and important start to lose power. But I think WWII as a venue for “war is awful and pointless” is much more fraught than maybe any other American conflict, including the War on Terror—which has produced plenty of those stories.

What is my actual conclusion? That it’s interesting to see a video game use its mechanics and its narrative structure to tell a message about the pointless horror of the events it depicts. But also, that the reason why WWI, and not WWII, is the most logical setting does not stem from a fundamental difference in the character of those wars.

For draftee soldiers, young men ordered to far-off lands to fight against people they’ve never met, for people they’ve never met, soldiers whose motivation is the same “quite simple” one as it’s always been—to survive and return home—the story could have been told in the Ardennes, or at Omaha Beach, or Iwo Jima as easily as Cambrai or Gallipoli. WWI does not occupy a privileged position as uniquely horrifying.

But, also, that it’s worth examining why it feels like there is a fundamental difference. And that, on reflection, the construct of WWII as “the good war” works conspicuously to serve the interests of the people who, on the whole, benefited most from it. And, not coincidentally I think, that this group of people is the same who view the praxis of history not as a learning opportunity, but as a means for moral instruction.

The United States is good and does good things; you should love America. The United States fought in WWII; therefore, fighting in WWII must have been good. If fighting in WWII wasn’t good, then you’re accusing America of being something other than good; therefore, you must make those accusations out of a desire to convince people to hate America.

Alternatively: if fighting in WWII wasn’t good, you must make this accusation out of a desire to see the Axis triumph instead.

But many things can be true simultaneously. The occupation by Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan produced greater suffering, for many people, than domination by the Allies. At the same time, to a victim of the Burmese famine, the goodness of the Allies is not so absolute. A world resulting from an Axis victory would be far less preferable than the one we have. At the same time, our real, historical post-war world entrenched systems of oppression and subjugation that were directly consequent to that war; this happened, it has lingering effects, and it can’t be downplayed.

Allied soldiers fought on a side whose victory structured the world, good and bad, that we know today. Many of them felt called to duty; many others were conscripted to it. Their heroism is real, and meaningful. At the same time, WWII was still awful, and destructive, and tragic, and it’s a shame that it happened and that people had to endure it.

And that is real and meaningful, too.

FOOTNOTES

- ^ John Kipling. That said, at least officially, “My Boy Jack” was not written about his son; he seems to have handled that quite privately.

- ^ Dolchstoßlegende. Heroic German soldiers who could have won the great war were betrayed by the civilian leadership. The United States adopted this same story in a big way after Vietnam; in Germany, though, it was core to Nazi ideology.

- ^ Breaker Morant came out in 1980. Gallipoli was released the following year. Both lean heavily on a version of Australian history that presents their characters as being sacrificial victims to British aims.

- ^ From here.

- ^ J. Douglas Harvey. Boys, Bombs, and Brussels Sprouts, published 1981.

- ^ Paul Fussell. Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War, published 1990.

- ^ Doris Miller was a United States Navy cook who was awarded the Medal of Honor (the first Black man to receive it) for his actions at Pearl Harbor manning an antiaircraft gun; he was later lost aboard the USS Liscome Bay; Benjamin Davis—one of only two Black officers at the time—led the Tuskegee Airmen.